In coming days, Minister Jason Clare will release the long-anticipated final report from the Australian Universities Accord panel.

Over the past 35 years, Australia’s higher education has largely been influenced by the 1987 reforms introduced by education minister John Dawkins. Of course, there have been several reforms since then, with varying degrees of success.

In September 2016, Tim Dodd reported that Dawkins said the 1987 reforms are completely out of date for current circumstances and the fact that they have lasted for 30 years is ‘actually a bad thing.’

Therefore, the stakes could not be any higher. For the betterment of our people and for future generations, further reforms are needed. Universities need increased Commonwealth funding (and financial certainty – longer than one election cycle), and students deserve increased support to equip them for success in work and life.

Depending on how the government responds to the recommendations for change from the Accord panel, Minister Clare will either be seen as a reformer, or someone who missed the opportunity to do so. Success will hinge on which recommendations are implemented (and lead to a transformation of universities and improved educational outcomes). It will also take some time for change to be embedded, so leadership is vital.

Purpose of this commentary

The aim of this commentary is to provide background on the Ministers who have had responsibility for university policy and funding, how long they held their post, and who have been responsible for instigating those university reviews.

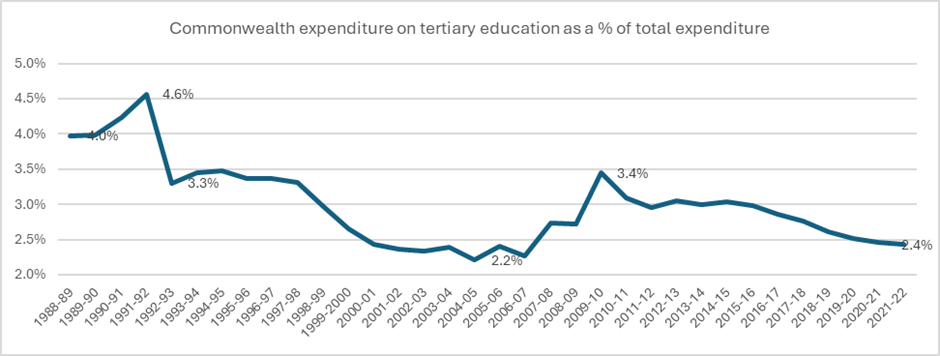

It also highlights that, as an outcome of these reviews, the Commonwealth expenditure on tertiary education as a proportion of total expenditure has declined. I also suggest that a whole of public sector approach if policy makers and university leaders are to be effective in driving forward the reform agenda.

Education ministers post Dawkins

Dawkins’ tenure as Minister began in July 1987 and ended in December 1991, for a total of four years and 156 days.

Since Dawkins left the post, there have been 20 federal ministers with responsibility for university education. Of these ministers, three held the post for four years or more: Simon Crean, David Kemp, and Brendan Nelson. Five ministers held their position for under three years but more than two: Simon Birmingham, Julia Gillard, Dan Tehan, Chris Evans, and Christopher Pyne.

There were three Ministers who held their post for under two years but over one year: Kim Beazley, Amanda Vanstone, and Julie Bishop. There were seven other ministers who held the post for less than a year. The current Minister Jason Clare has held the post for one year and 261 days (as of Sunday 18 February).

A much-reviewed sector

Let us see which Ministers have had oversight of the most significant reviews of higher education since Dawkins.

- Amanda Vanstone (Minister for Employment, Education, Training and Youth Affairs – 1 year, 212 days) initiated the review of higher education financing and policy in January 1997. The review led by Roderick West delivered a final report in April 1998 to David Kemp (Minister for Education, Training and Youth Affairs).

- Brendan Nelson (Minister for Education, Science and Training – 4 years, 62 days) began a review to determine appropriate mechanisms and levels of funding for higher education in April 2002. The final report ‘Our universities: Backing Australia’s future’ was delivered in May 2003.

- Julia Gillard (Minister for Education – 2 years, 207 days) initiated the next review of Australian higher education in March 2008. Denise Bradley led the review with the purpose of examining the state of the Australian higher education system, exploring future directions, and consider options available. The final report was released in December 2008.

- Chris Evans (Minister for Tertiary Education, Skills, Jobs and Workplace Relations – 2 years, 172 days) commissioned the higher education base funding review. This is best known as the Lomax Smith review, commissioned in October 2010, with the final report delivered in October 2011. The purpose of this review was to identify principles to support public investment in higher education.

- Joe Hockey (2 years, 3 days) commissioned an audit in October 2013 to assess the role and scope of Government, as well as ensuring taxpayers’ money was spent wisely and in an efficient manner. The Report of the National Commission Audit was released in May 2014.

- Christopher Pyne (Minister for Education and Training – 2 years, 3 days) commissioned a review of the demand driven system in November 2013 and the final report released in April 2014. David Kemp and Andrew Norton led the review which had the purpose of examining the impact of the demand driven system.

- Dan Tehan (Minister for Education and Training – 2 years, 116 days) announced in October 2018 that Peter Coaldrake was commissioned to lead the review of the higher education category standards. The final report was released in October 2019 and the Government delivered its response in December 2019.

- Dan Tehan (Minister for Education – 2 years 116 days) and Michaelia Cash (Minister for Employment, Skills, Small and Family Business – 2 years, 214 days) released the final report on the review of the Australian Qualifications Framework in September 2019. Led by Peter Noonan, the purpose of the review was to ensure Australia continues to meet the needs of students, employers, education providers and the wider community.

Commonwealth funding

Since the Dawkins reforms, the Commonwealth has been the main public funding source for higher education. In 2021 Australian government grants accounted for 36.1 per cent of income for Australian universities.

State and local government funding is minimal and accounted for 2.1 per cent as the Commonwealth has assumed overall responsibility for higher education.

International students contributed 22.4 per cent of universities’ income.

Australian government payments for HECS-HELP, FEE-HELP, VET FEE-HELP and VET Student loan Program, and SA-HELP accounted for 15.9 percent.

The remainder (23.5 per cent) came from consultancy, investment, donations and other sources.

Now, let us see how the level of Commonwealth expenditure for the purpose of higher education in Australia has changed overtime.

Commonwealth expenditure on tertiary education – past ten years

According to the Australian Bureau of Statistics’ Government Finance Statistics, Commonwealth expenditure on tertiary education accounted for 2.4 per cent for the financial year 2021-22, down from 3.1 per cent in 2012-13 (See table below).

Over the past ten financial years, Commonwealth expenditure increased the most in social protection (by 1.7 points), in public health services (by 1.5 points), and defence (by 1.0 points).

Interestingly, the Commonwealth expenditure on pre-primary, primary and secondary education increased by from 3.7 per cent in 2012-13 to 4.1 per cent in 2021-22.

It is worth noting that the non-government school sector has benefited the most. According to the Productivity Commission 2023 Report on Government Services, 59 per cent of Commonwealth funding for schools went to the non-government sector in 2020-21.

Over the last decade, the tertiary education sector received a lower share of income from the Commonwealth compared to the pre-primary, primary, and secondary education sectors.

In 2021-22, the tertiary education sector received 58.7 per cent of the amounts the Commonwealth spent on the pre-primary, primary, and secondary education sectors compared to 82.4 per cent in 2012-13.

Based on the 2021-22 figures, an additional Commonwealth investment of $3.6 billion would have brought the Commonwealth expenditure on tertiary education as a proportion of total expenditure to 3 per cent. This would have delivered improved educational outcomes for thousands of students.

Table 1: Commonwealth General Government Expenses by Purpose | |||||

| 2012-13 | 2021-22 | Ten-year change | ||

$m | % of total expenditure | $m | % of total expenditure | ||

Total Expenses | 384,002 |

| 623,067 |

|

|

Education | |||||

Pre-primary, primary and secondary education | 14,231 | 3.7% | 25,767 | 4.1% | 0.4% |

Tertiary education | 11,729 | 3.1% | 15,136 | 2.4% | -0.6% |

Other education | 6,742 | 1.8% | 9,382 | 1.5% | -0.2% |

Total education | 32,703 | 8.5% | 50,285 | 8.1% | -0.4% |

Source: Australian Bureau of Statistics, Government Finance Statistics, Australia, 2021-22, Table 4, released on 26 April 2023. | |||||

Longitudinal trend of Commonwealth expenditure

To build a longitudinal picture of the Commonwealth expenditure on tertiary education since the Dawkins reforms, I have retrieved the annual tables from the Australian Bureau of Statistics on government finance.

As often happens, there are year-on-year revisions to previous years’ data. Also, there have been various splits to the tertiary education sector, e.g. university, technical, and further education, and other tertiary sectors. These splits may result in expenditure placed in the ‘other’ category.

In brief, the long-term trend over the past thirty-five years indicates:

- Commonwealth expenditure on tertiary education as a proportion of all expenditure stood at 4.0 per cent in 1988-89 and increased to 4.6 per in 1991-92.

- The 1989-92 period was when institutional amalgamations occurred under John Dawkins. Furthermore, 1991-92 was the year for which tertiary education expenditure as a proportion of all expenditure was at its highest level.

- Expenditure decreased to 3.3 per cent in 1992-93 when Kim Beazley was Minister for Education.

- Over the next few years, Commonwealth expenditure continued to decline, dropping below three percent in 1999-2000 (2.7 per cent) when David Kemp was minister.

- The lowest proportion recorded was 2.2 per cent in 2004-05 when Brendan Nelson was minister, but then improved over the next four years to 2.7 per cent in 2008-2009.

- Under Julia Gillard as Minister for Education, the proportion of Commonwealth expenditure increased to 3.4 per cent in 2009-10, up by 0.7 points from 2008-09.

- Expenditure increased by 2.9b from $8.76b to $11.67b in response to the Review of Australia’s Higher Education and the Review of the Innovation System.

- Over the next six years expenditure stood around 3.0 per cent.

- Since 2016-17, expenditure has been below 3 per cent. For the latest available year (2021-22), expenditure stood at 2.4 per cent.

Outcomes from reviews

An outcome from the various higher education reforms is that the financial contribution from the Commonwealth has diminished over time. Although the Commonwealth has increased funding following some of the reviews, these additional contributions have not been sustained over the long term.

The reviews have not brought about a whole of government approach to coordinate activities associated with universities. This is particularly relevant to the international education space where efficiency and effectiveness of government programs can be made. A whole of government approach can lead to improved processing for student visas (e.g., government agency assumes responsibility if a student visa is delayed beyond a reasonable time).

Also, the reviews have not bolstered universities’ ‘safety net’ to mitigate a downturn in student demand or unforeseen shifts in market forces. Funding agreements between the Commonwealth and universities which go beyond one electoral cycle (e.g., five years) will be a great way for universities to build financial resilience.

What lies ahead?

Once the Federal budget is released in May, it is likely that the Commonwealth will have a set of spending measures to boost universities’ finances, ideally in line with the 2009 budget. These measures will help universities in the short term (two to three years) as the longitudinal data suggests. However, we should not expect that there will be a significant boost for universities’ long-term financial sustainability.

We also must keep in mind that there are so many competing priorities for the federal government. With geopolitical tensions rising, issues of national security and border protection, ageing population and environmental challenges, expenditure on tertiary education is not at the top of the agenda.

Better coordination of all public sector agencies is required to make the whole reform process a success.

Universities will continue to depend on international students and commercial activities to fund staff wage increases, building and infrastructure maintenance, plus a range of mission-based priorities. I would say that the outlook for Australian higher education is bleak. Let’s see what the outcome of the Accord process turns out to be.

Sooner or later university leaders will have to address how best to move forward, figuring out what the right size and shape of the sector is to make ends meet. University advocacy will also need to adopt a whole-of-public sector approach if it is to be effective in the long run.

Angel Calderon is Director, Strategic Insights at RMIT University. In 1989, Angel began his working career as a planning research assistant at Footscray Institute of Technology.