Sign Up for Our Newsletter

Subscribe to us to always stay in touch with us and get latest news, insights, jobs and events!!

It was April 2022.

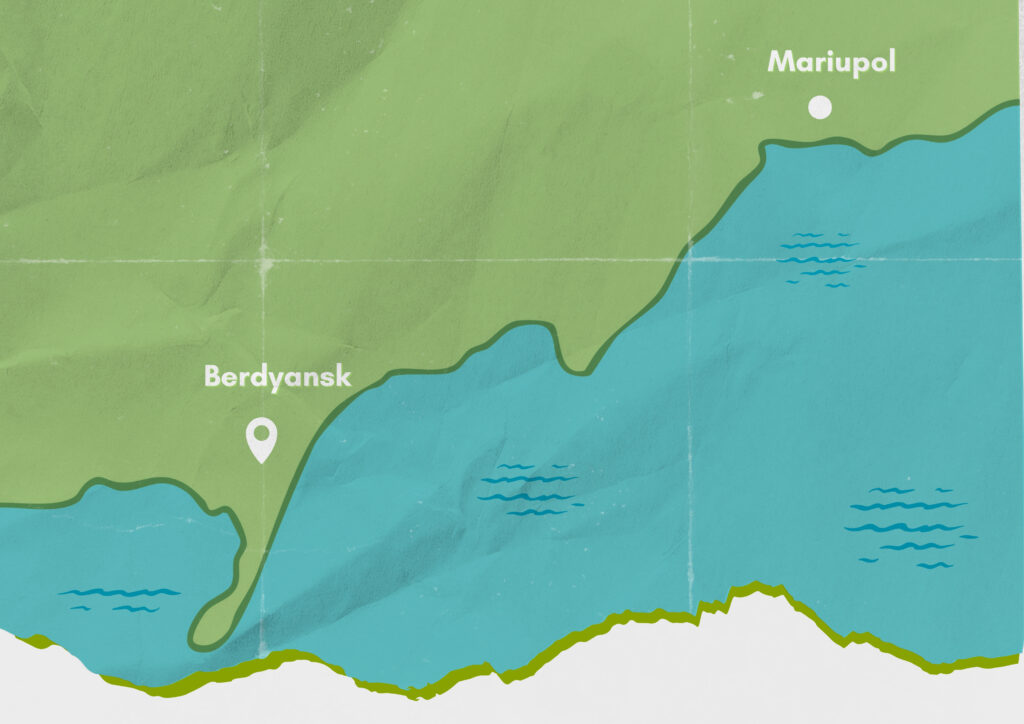

February’s snow was a memory banished by Spring. For decades, Russians had been coming to the small coastal city of Berdyansk region in southeastern Ukraine to visit for Summer.

This year they had come early. In tanks.

As the Ukrainian flag was hauled down in the town square and replaced by the Russian tricolour, it was obvious that holidays were not on their mind.

Yana Sychikova was the last of the leadership of the Berdyansk State Pedagogical University left behind enemy lines when she got word in April that the Russian authorities wanted to arrest her, along with other government and organisational leaders.

She was forced into a deadly game of hide and seek for a month, evading capture with her small family by hiding in the apartments of friends in and around her hometown of Berdyansk, in Southern Ukraine, before it was obvious that leaving town was the only option.

Yana, her teenage son and husband then spent two solid days on the so-called Road of Death, avoiding mines, artillery bursts and enduring more than a dozen interrogations at checkpoints. She had even prepared herself to take up arms and head to Ukraine’s front line to help combat the Russian invasion before she reached the relative safety of Ukrainian territory.

This is not someone who is easily frightened.

But despite all those near misses, the thing that spooks Yana Sychikova right now is whether to buy another wooden spoon.

She left behind so many kitchen items before fleeing her hometown. Buying duplicates of items from her kitchen drawer in Berdyansk feels like a surrender to acceptance that she might not be home any time soon, or maybe ever.

“This transitional state is a frightening feeling,” she says, from her latest abode, 1000 km west, deep inland near Ukraine’s border with Poland.

“It’s what I call the syndrome of deferred life. The idea that we just have to endure for a bit, and then we’ll return, and everything will be as before. But that “bit” has already become four years. You don’t buy household things because you already have them back home in Berdyansk — why buy them again? And so on.

“It’s emotionally draining and prevents you from living a full life; it postpones decisions and actions.

“It’s not just a personal feeling; it’s also a systemic problem. Even the authorities keep using the word “temporary.” For some people, temporary has been 10 years already. Can you imagine waiting for 10 years with your major life decisions and even some small decisions suspended?”

It was April 2022.

February’s snow was a memory banished by Spring. For decades, Russians had been coming to the small coastal city of Berdyansk region in southeastern Ukraine to visit for Summer.

This year they had come early. In tanks.

As the Ukrainian flag was hauled down in the town square and replaced by the Russian tricolour, it was obvious that holidays were not on their mind.

Yana Sychikova was the last of the leadership of the Berdyansk State Pedagogical University left behind enemy lines when she got word in April that the Russian authorities wanted to arrest her, along with other government and organisational leaders.

She was forced into a deadly game of hide and seek for a month, evading capture with her small family by hiding in the apartments of friends in and around her hometown of Berdyansk, in Southern Ukraine, before it was obvious that leaving town was the only option.

Yana, her teenage son and husband then spent two solid days on the so-called Road of Death, avoiding mines, artillery bursts and enduring more than a dozen interrogations at checkpoints. She had even prepared herself to take up arms and head to Ukraine’s front line to help combat the Russian invasion before she reached the relative safety of Ukrainian territory.

This is not someone who is easily frightened.

But despite all those near misses, the thing that spooks Yana Sychikova right now is whether to buy another wooden spoon.

She left behind so many kitchen items before fleeing her hometown. Buying duplicates of items from her kitchen drawer in Berdyansk feels like a surrender to acceptance that she might not be home any time soon, or maybe ever.

“This transitional state is a frightening feeling,” she says, from her latest abode, 1000 km west, deep inland near Ukraine’s border with Poland.

“It’s what I call the syndrome of deferred life. The idea that we just have to endure for a bit, and then we’ll return, and everything will be as before. But that “bit” has already become four years. You don’t buy household things because you already have them back home in Berdyansk — why buy them again? And so on.

“It’s emotionally draining and prevents you from living a full life; it postpones decisions and actions.

“It’s not just a personal feeling; it’s also a systemic problem. Even the authorities keep using the word “temporary.” For some people, temporary has been 10 years already. Can you imagine waiting for 10 years with your major life decisions and even some small decisions suspended?”

By TIM WINKLER

After being invaded, hunted by Russians, forced to flee along the road of death and evading ongoing threats and bombardments, Ukrainian academics Yana Sychikova and Igor Lyman are rebuilding their workplace as a University Without Walls.

By Tim Winkler

Before the occupation, the city of just over 100,000 traditionally swelled to six times that number in peak season, enjoying its relatively newfound status as the aquatic playground on the Azov coast – slowly overcoming decades of decline after Soviet manufacturing peaked in the port city in the 1950s. It had evolved into aquatic-playground-meets-Soviet-era-port with a distinctive identity coveted by residents.

Berdyansk’s identity has long been a complicated, lopsided duet between Russian occupiers and Ukrainian inhabitants. Many of the Ukrainians are of Russian heritage and Russian language was more commonly spoken than Ukrainian prior to the war, but community cohesion has been tested by repeated periods of possession and attempts at control by Moscow.

The area around Berdyansk was initially an outpost of Ukrainian Cossacks, valued for its strategic location, and no doubt also plentiful seafood.

Russian Earl Mikhail Vorontsov, appointed Governor General of the region after success in defeating Napoleon, decided to build a major port on the Azov Sea, with Naval scouts selecting safe waters near the Berdyansk Spit. A landing stage was built in 1827, city status was granted in 1835 and by 1838 first glow of the town’s distinctive white and red banded lighthouse marked the importance of the port. More than 14,500 vessels reported using the lighthouse to guide them in the busy waterway over the next 30 years alone.

Flirting with achieving independence during the Russian Revolution, Berdyansk instead became an important industrial base as part of the Soviet Union, losing almost its entire, substantial and established Jewish community under German occupation in 1941-42 before resuming a part in the economic rise and decline of the USSR.

The area around Berdyansk was initially an outpost of Ukrainian Cossacks, valued for its strategic location, and no doubt also plentiful seafood.

Russian Earl Mikhail Vorontsov, appointed Governor General of the region after success in defeating Napoleon, decided to build a major port on the Azov Sea, with Naval scouts selecting safe waters near the Berdyansk Spit. A landing stage was built in 1827, city status was granted in 1835 and by 1838 first glow of the town’s distinctive white and red banded lighthouse marked the importance of the port. More than 14,500 vessels reported using the lighthouse to guide them in the busy waterway over the next 30 years alone.

Flirting with achieving independence during the Russian Revolution, Berdyansk instead became an important industrial base as part of the Soviet Union, losing almost its entire, substantial and established Jewish community under German occupation in 1941-42 before resuming a part in the economic rise and decline of the USSR.

Before Ukraine achieved independence in 1991, it had been controlled by Russia for centuries and Russian language had been more commonly spoken in some Eastern Ukrainian areas than Ukrainian, with a significant portion of the population being of Russian ancestry. False allegations of mistreatment of the Russian minority had been used by Putin as one of the pretexts for initiating the invasion. Since the invasion, Ukrainian language uptake has significantly increased.

Prior to the Crimean invasion in 2014, hundreds of thousands of Russian holiday makers used to flood Berdyansk in the warmer months, with direct overnight trains from Moscow – basking in the spas, sliding on the waterparks and dining on the famed local delicacy of Berdyansk Bychok – fillets of Goby fish in a tomato sauce.

Following the outbreak of hostilities with Russia in 2014, the majority of holiday visitors to Berdyansk were Ukrainian, and in 2021, more than 1.5 million people visited the city.

Schools of Goby breeding off the coast of Berdyansk have long been the staple of the town’s fishing fleet, and the availability of the fish was a key factor in staving off starvation during the second world war.

The Goby is one of a number of cultural icons memorialised in sculptures across the city.

On 24 February 2022, the tempo of the eight-year-old war between Russia and Ukraine abruptly increased, with President Putin’s forces launching a multi-pronged attack to occupy Ukraine, in an offensive that Russian Generals had predicted would last just three to four days. More than three years later, Russia has gained limited territory and is estimated to have lost more than a million soldiers, with no clear end in sight.

Three days after the 2022 offensive started, Russian troops rolled into the main square of Berdyansk.

Within weeks, the mayor of Berdyansk disappeared, believed to be abducted by the Russians along with some of his deputies, a Russian Military Commandant was installed, a curfew was enforced. Ukrainian mobile phone towers were disabled, so there was no ability to use a phone in a 30km radius of the town. Many journalists, politicians and others opposing the new regime were abducted. How many is not known – but independent reports of abduction and torture illustrate the intense danger.

“BERDYANSK, Ukraine — Russian military patrols prowl the streets, Russian channels fill the airwaves, and the Russian-imposed authorities take a cut of the fishermen’s catch. The mayor has disappeared, phone service is dead, and protests are rare after occupying forces fired into the air at rallies against them in March.”

Ukrainian journalist Viktoriia Roshchyna, April 12, 2022 reporting from Berdyansk, less than a year before her capture and subsequent murder while investigating the fate of abducted Ukrainians held by Russian authorities.

Yana Sychikova was born to Ukrainian officers in the soviet military, who were stationed in the Soviet Union’s far east, before returning to Berdyansk when Ukraine won independence in 1991.

She excelled at physics when she enrolled in BPSU, relieved to see a career open up that wouldn’t consign her to high school teaching.

“It wasn’t even a decision — it felt like something given, as if I was born for science and no other path was possible,” she says.

Building a research career around semiconductors and Dielectrics, she was appointed Vice-Rector in 2021, fast-tracked into leadership. But almost all her institutional leadership has been without a University campus to sit in. Professor Sychikova had been appointed Vice-Rector for Research at Berdyansk State Pedagogical University just four months before the city was occupied by Russian forces, on 27 February 2022 – the third day of Russia’s large-scale offensive.

Spring was near, and the crowds of holiday makers that usually descended on the small seaside city in Summer were not due for another month or two.

“I didn’t leave right away — like most people. At first, everyone was hearing the same message: that the war would be over in three days, or two weeks, and so on. It seemed possible just to wait it out.

“Besides, I was part of the university’s management — I felt responsible for the well-being of our staff and students. During the first weeks of occupation, our main task was simply to find food for the students who stayed in the dormitory. The city was facing a humanitarian crisis — there was no supply of food, medicine, or fuel at all.

“We didn’t know what to do, because the Ministry of Education and Science wasn’t giving us any guidance. When we asked whether we should evacuate and relocate the university, the answer was: “You have autonomy.” But what were we supposed to do with that autonomy under such conditions? We were waiting, not knowing what would come next.

“After about two months, the Rector and the first Vice-Rector managed to leave. I stayed behind for a while — someone had to manage the situation, support colleagues, and keep things going.

After abducting municipal leaders, the Russian occupation forces were seeking to silence or control leaders of key organisations. As the most senior staff member at the university – an organization that was refusing to give up its Ukrainian identity and train students in Russian, for Russia, Professor Sychikova was now a key target for the military authorities.

“During the last month, I had to hide in other people’s apartments because the occupation authorities were looking for me. It was extremely dangerous,” she says.

At night, the city of Berdyansk was quiet, under curfew with Russian soldiers and separatists patrolling the streets, creating an eerie calm. But there was another silence, which, when it came, was even more chilling.

When Russian forces besieged the nearby city of Mariupol, around 80 km away, the relentless shelling could be heard in Berdyansk. At the same time, tens of thousands of residents fleeing Mariupol flooded through Berdyansk as they sought to reach safety behind Ukrainian lines.

“I still haven’t been able to watch the film Mariupol. For me, it’s too painful,” Professor Sychikova said.

“That city was close to Berdyansk, and I heard every day what was happening there and had many friends there. We could hear every explosion from Berdyansk. The most painful moment was when the city went silent — that meant it had been taken.”

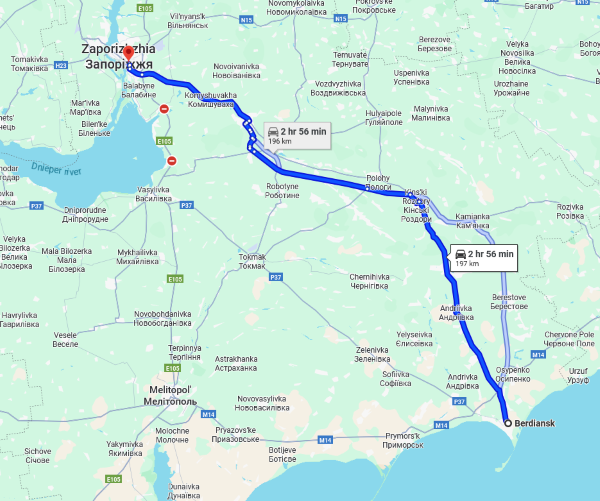

With the fall of Mariupol and the rising danger of Russian authorities seeking to

capture her, it became clear to Professor Sychikova and her family that there

was no alternative but to evacuate to Ukrainian territory – even though the 200

km ‘Road of Death’ between Berdyansk and Zaporizhzhia was now perilous.

“It was both the road of death and the road of life,” Professor Sychikova says.

“Leaving was extremely dangerous; not everyone made it. But once you crossed it, you were free. After living through the occupation, you come to truly understand the meaning of freedom — it’s not an abstract concept, it’s something as vital as breathing.

“We left in our own car. The distance from Berdyansk to Zaporizhzhia is about 200 kilometers — normally a three-hour drive — but the evacuation took much longer. For some people, it took over two weeks, because the occupiers simply wouldn’t let anyone out.

“They kept civilians waiting in endless lines and used them as human shields, positioning their artillery nearby to fire at Ukraine, knowing Ukraine wouldn’t shoot back — because thousands of civilians were standing there, waiting for permission to leave.

“We were lucky — our journey took only two days. But it came at an enormous risk: driving on mined roads, under shelling, through dozens of checkpoints with searches and interrogations — what they called “filtration camps.” Not everyone passed them. Some people were taken away, and their fate remains unknown.

“We could take only two things with us from the whole university – the university seal and its charter.”

On the Road: Professor Sychikova’s son and cat during the family’s evacuation from the Berdyansk to Ukrainian-held Zhaporizhzhia.

After most staff and many students had reached relative safety of Ukrainian territory, they still faced the constant threat of air raids, hunger and a need for shelter. But Professor Sychikova is momentarily shocked when asked why she persisted in trying to keep working for the University.

“Did a conscious, responsible manager really have any other choice? I am responsible for everyone who works at our university, so it never even crossed my mind to change my life or walk away,” Professor Sychikova says.

“Of course, not everyone thought that way. There were cases where rectors and vice-rectors of some universities chose to collaborate with the occupation authorities — betraying their entire academic community. That is truly horrifying,” she says.

“At the beginning of the war, when we still didn’t understand where the front was, where the rear was, or how the situation would unfold, I thought that I might have to go and fight. I accepted that calmly and was ready for it — and I still am.

“But even here, behind the front lines, we need managers and teachers. Children must continue to grow, and we, as educators, are responsible for their development and formation as citizens and patriots of our country.”

The Berdyansk Pedagogical State University was established in 2002, building on a number of predecessor institutions stretching back more than a century that had been the heart of higher education in the city. The historic, picturesque campus in the heart of the city had an enrolment of just over 5,000 students prior to occupation – and had been ranked among the most beautiful campuses in Ukraine.

While student numbers dropped when the university was displaced, its leadership realized that its importance to the displaced community had risen – as well as its opportunity to contribute to the nation as a whole.

The immediate job was to find food and shelter for staff and students who had fled the occupied city – but the conflict also brought the university closer to thousands of others from the city who faced the same challenges. This prompted an urgent re-evaluation of what the role of the university was, and how it could better serve its community.

In between rallying to find food and shelter for students Professor Sychikova soon turned the time she could grab for her own research to support the war effort, researching the development of sensors to detect missile traces. In a war distinguished by its aerial weaponry, the science of detection in the air can be the difference between life and death.

“Science during wartime is critically important — it cannot stop even for a moment. This is our contribution to the war effort: we are holding the scientific front,” Professor Sychikova says.

Stripped of physical resources, the university was literally defined by its people, but also had heightened responsibilities – researching and educating the future Ukrainian workforce not just in relation to defence, but also rehabilitation and recovery. This included documenting the experiences of displaced universities, to capture lessons learned in real time.

With a floor of office space secured at Zaporizhzhia National University, the BSPU had a place established for staff, around 30 kilometres from the front in Ukrainian Territory, but no space for teaching and little opportunity for students to easily travel to classes.

With literally no walls of their own, let alone research equipment, few laptops or teaching resources, Professor Sychikova suggested implementing a concept that had been around for 70 years, but only sporadically implemented – reorganising as a ‘university without walls’.

The universities without walls concept was first applied to adult education in the US in the 1970s but had existed as a concept for some time.

The idea is that the university is not organized around a campus but rather around people and “knowledge societies” embedded far more closely with community and policy makers was more recently developed as a vision for the future by the European University Association in 2021.

“Our university is now a University Without Walls. This doesn’t mean we have no buildings at all — rather, it means that no one is required to be “on campus.”

“Officially, the university has been relocated to Zaporizhzhia, but that city is practically on the front line. It is extremely dangerous there — constant shelling and bombings with missiles and aerial bombs. So most of our community is not physically present in Zaporizhzhia,” Professor Sychikova says.

The university recognised the community of Berdyansk in exile still had a need to study, even as they atomised to locations across the globe, seeking refuge where they could find it. So they set about deploying the lessons learned during COVID, but with allowances for the intrusion of war into the lives of everyone in their community.

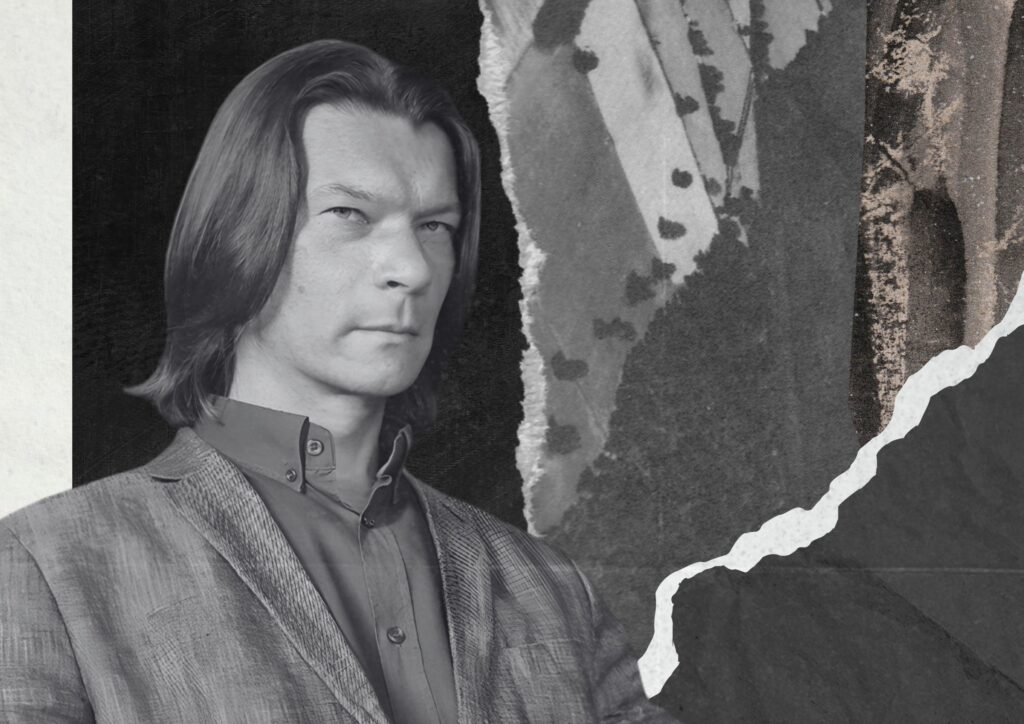

Igor Lyman is Berdyansk to the core – born and bred by the Azov, like generations of his family before him. He had crafted a career as one of the leading historians of the Southern Ukraine, collecting artefacts from across the region to build a remarkable collection at the University and writing a dozen books about the region. His wife and fellow historian Victoria Konstantinova recognised patterns of conquest repeated from the past in early 2022.

“Everyone said: “Putin will not attack.”” Professor Lyman recalls.

“We watched his speech on TV live on February 21, 2022. Formally, the speech was about the recognition of the so-called “Donetsk People’s Republic” and “Luhansk People’s Republic.” The speech lasted more than an hour, but there were only a few minutes about these “Republics”. The rest was, in fact, about the non-recognition of Ukraine’s statehood.

“My wife and I, as historians, saw what “2+2=” and clearly understood what would happen next. So the next morning we were one of the few families to leave Berdyansk. When we, with our teenage son, were driving from Berdyansk to Zaporizhia, there were almost no cars on the road except us.

“In less than two days, Russia launched a full-scale invasion, and 3 days later Berdyansk was occupied by Russian troops. But literally after a few days, this road turned into hell, and the distance of 200 km, through 15-17 enemy checkpoints, began to take a week.”

Professor Lyman left behind not only his home, friends, family and workplace, but also his collection of historical artefacts from the region, collected over three decades, which had been a critical foundation in his research specialisation.

Within a week of leaving, he was accommodated in the grounds of a university in Chernivitsi, in Western Ukraine, in a camp for displaced persons – his home for the next six months.

“We left Berdyansk with our dog Matilda, an American Cocker Spaniel. And in the bomb shelter, she was the center of attention: dozens of children flocked around her, petting and playing with her. As psychologists said, this helped them avoid stress and panic from the sounds of the air raid siren. But Matilda was exhausted by all this attention,” Professor Lyman says.

Chernivitsi National University established accommodation specifically for displaced university staff – helping inform his new disciplinary focus.

As the BSPU community regrouped, Professor Lyman took on a role as the lead international contact for the University, while also pursuing new directions in research and teaching.

Now based in the capital Kyiv, Professor Lyman is working with Professor Sychikova on the world’s first in depth examination of displaced universities and the lessons that can be learned from Ukraine’s experience.

In the first days of relocation to Zhaporizhzhia it was clear the university had to be much more than a teaching and research institution.

“We try to provide our students and staff with everything they need — purchasing power banks, charging stations, generators, and laptops. We also periodically organize humanitarian aid in the form of food packages,” Professor Sychikova says.

As time moved on, and the university found a new asynchronous rhythm as a university without walls, staff and students settled into a new reality of balancing the joy of freedom with the loss of critical parts of their past life.

BSPU now has an enrolment of about 4,700 students, including students at the front, continuing their studies in between battles; students risking punishment by Russian authorities, covertly continuing to study with the university while remaining in occupied territories; and student refugees in temporary accommodation scattered across the world.

This dispersed BSPU diaspora presents a monumental challenge, but also an opportunity – reinventing the university as an atomized but connected community, rather than being bound by real estate or locality.

“Berdyansk State Pedagogical Universities is now a university without walls. This means that we relocated, but we don’t work in just in certain place, in certain city. We work at the same time in different locations. We work online. And because of this, We have many challenges, but at the same time, we had a lot of opportunities.” Professor Lyman says.

As with many countries of the world, Ukrainians need to adapt to teaching and learning online during the pandemic and campus life had barely returned to normal when the occupation began.

“When the university was forced to move to Zaporizhzhia, this online mode was preserved, which helped a lot,” Professor Lyman says.

Frequent shelling and air raids by Russian drones meant that regular class and exam times were difficult to maintain, so students had to be given the flexibility to complete study when they were able to access it through asynchronous learning, and completing assessments within a window of time.

The university recognised it needed to adopt a much more flexible approach to accommodating student circumstances – reorganising operations to be more truly student-centric. A student could hardly put down their gun mid firefight or sit near the router in their home, praying to avoid bombs or the frequent electricity blackouts raid just to sit for their exam on time.

“Due to enemy attacks, including airstrikes, sirens are not being activated simultaneously in different cities of Ukraine. In addition, electricity and internet outages caused by enemy attacks are a common occurrence in different cities. “Therefore, we widely practice asynchronous learning, where students complete their practical and individual work (tasks) in the Moodle system when they have access to the Internet and are not forced to go to shelters,” Professor Lyman says.

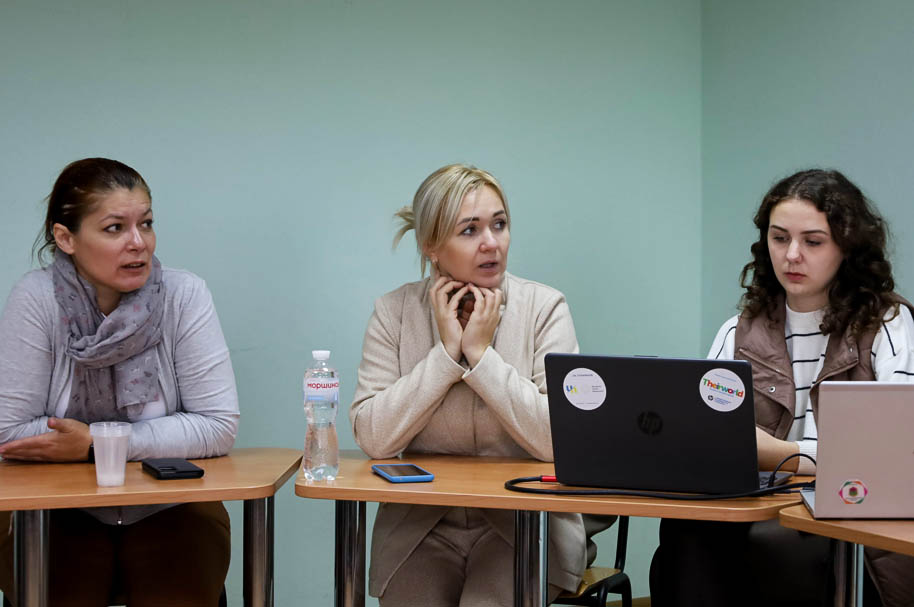

With the trauma of war and limitations of online learning, university staff also learned that an effective ‘University without walls’ must also conduct in-person teaching and meetings for staff – which are organised in different cities of Ukraine to accommodate the scattered university community, Professor Lyman says.

Lessons are conducted on Zoom and laboratory work is conducted in intensive classes in safe cities in Ukraine.

Assessments must be completed within a two to three week examination window, allowing students to complete their studies in most situations, Professor Sychikova says. This had proven beneficial to students in many different situations and should be continued post-war, she said.

“I believe this flexibility should become a standard practice, not just a temporary strategy. Of course, it places an additional burden on lecturers — but for now, it’s the only thing that truly works,” Professor Sychikova says.

“Our students are in the occupied territories, on the front lines, and scattered all over the world. We don’t have any in Australia, but many are in countries with very distant time zones — the U.S. and Canada, for example. The same is true for some of our faculty.

“Deans try to schedule classes at more convenient times, and teachers interact with students around the clock. There is virtually no separation now between work time and personal time.”

At the same time, staff also must find time for research to support the war effort, Professor Sychikova says.

“Universities are also working on research that helps to mitigate the effects of war, as well as on projects directly supporting defense needs. Science during wartime is critically important — it cannot stop even for a moment. This is our contribution to the war effort: we are holding the scientific front.”

Without labs, the university research repository and other key tools, many academics have been displaced not just from their homes and workplaces, but also from their discipline. This adds to the sense of frustration and loss for many, but others have recognised adaption is critical for survival, and to find new avenues to a sense of purpose.

Professor Sychikova still works in materials science, but has switched focus, now researching materials for photodetectors used to detect missile trails. “This is something we urgently need today, as Russia attacks us daily, and reliable air defense systems are vital for our survival,” she says.

She is also studying innovative pedagogical practices – in particular ways to support the training of specialists for high tech industries – critical workers to support the war effort and currently in short supply.

For Professor Lyman, the pivot was more challenging – severed from connection to not just that area of country that he was born into and had studied, but also his extensive collection of copies of handwritten documents from dozens of archives built up over decades.

Skilled in collecting oral histories as part of his work, he is now working with Professor Sychikova to research and document the experiences of displaced universities, channelling his considerable intellectual energies into an entirely new field.

“In 2023, my colleagues and I relaunched the Ukrainian Oral History Association, and one of its important areas of activity become the production and popularization of the methodology and ethical norms for conducting oral history interviews in wartime.” Professor Lyman says.

While the war precipitated new avenues of inquiry, the university also quickly became aware of the dangers presented for students and interview subjects behind enemy lines.

“The difficulty of accessing many Ukrainian archives, which are also under constant threat from airstrikes, plus the importance of documenting the history of the current war, has forced researchers to use oral history methods much more actively than before,”

Professor Lyman says.

“Many people rushed to record the interviews, often having neither training nor experience for this. And there was a real threat that this would harm not only science, but also pose a threat to the respondents themselves. After all, people were interviewed both in the occupied territories and at the front. And the publication of their interviews posed a threat both to themselves and to their relatives.”

Students in occupied territories also face constant danger – prohibited by Russian authorities from studying in anything other than Russian institutions. Recent reports from occupied territories indicate that residents live in a repressive system, enforcing fealty to Russia. They are reported to be required to adopt Russian citizenship in order to retain ownership of their house, get a job or access medical care. Secondary students in occupied areas have been banned from using or studying Ukrainian language and young people are being forced into militarization and indoctrination programs in Russia.

“Students who remain in the occupied territories take enormous risks — if the occupation authorities learn they are enrolled with us, they can be persecuted or taken away for interrogation or detention. The same danger applies to lecturers,” Professor Sychikova says.

The tremendous risks facing students who continue to study with displaced universities and also those who participate in research projects has led BPSU to consider data security.

Open access publications and information are critical to the sustainability of the university without walls – reducing costs and barriers to access. However, the university realised that lives will be put it risk and likely lost if data identifying students, teachers and research collaborators in occupied territories is not secured.

“I’m convinced that after the initial euphoria about Open Science, the world needs a new formulation — Responsible Science. “Do no harm” should be the new paradigm for working with data, because behind every spreadsheet and registry there are real people and real lives,” Professor Sychikova says.

The university must hide surnames, class lists and even timetables so that Russian authorities are not tipped off to students studying in occupied zones. They also have to communicate via private social network channels.

Documents must be signed online, using electronic signatures, which also require encryption.

Social meetings to build a sense of student identity and university connection are also critical – but must also be held online. Staff and students alike join in.

“Students understand that we professors are having the same struggles and in many cases this makes them more enthusiastic to study,” Professor Lyman says.

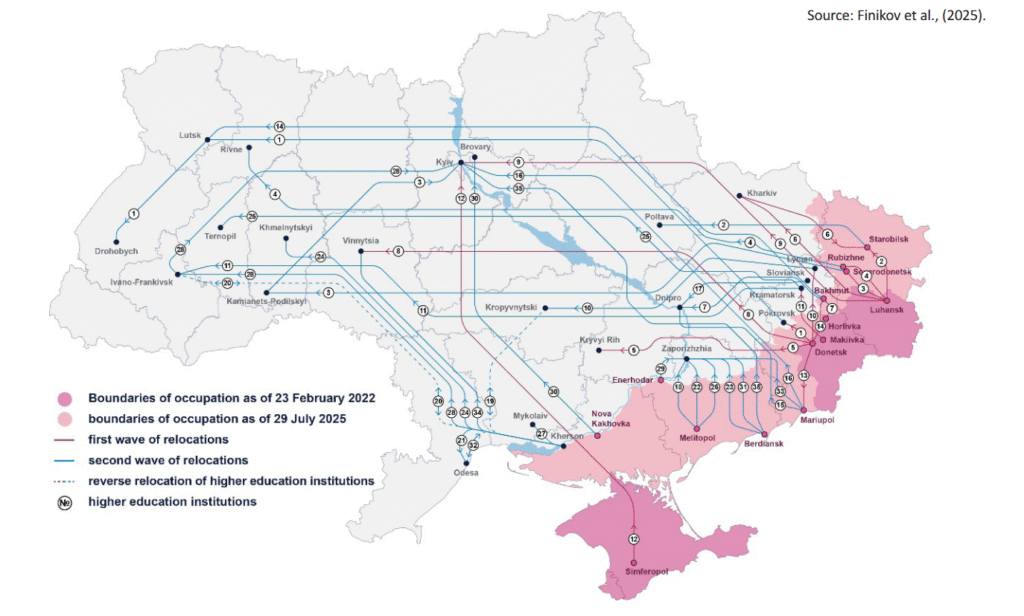

Professor Sychikova and Lyman are working with colleagues to document the experiences of more than 40 universities displaced by the war in Ukraine.

The researchers observed the impacts of the two waves of relocation – the first with Crimea and parts of Donetsk were occupied in 2014 and the second, occurring after Russia initiated its much larger offensive in 2022.

While a number of institutions initially sought refuge in the capital Kyiv, more strategic approaches to relocation became common, as institutions attempted to keep close to their relocated populations.

Occupied cities and institutions tend to be like objects trapped in amber – suspended in time, remembered as they were, often with little information emerging as to how life has changed.

“Occupied cities are like dark spots on the map of modern geopolitics, spaces that exist simultaneously in reality and outside of it,” Professor Sychikova wrote in a 2025 paper on the plight of universities displaced by occupation. “They become objects of strategic planning, diplomatic negotiations, and topics for bold headlines but almost never – objects of genuine understanding.

“Life in these cities seems frozen in time, yet it continues – with different rules, compromises, and fears. These are spaces where daily choices, silence, and invisible compromises create a parallel reality that remains imperceptible from the outside.

“Strategic plans hang suspended between past and future, and every bureaucratic metric conceals countless human stories.”

While displacement presented huge challenges, it also created opportunities, according to a new paper written with colleagues mapping the impact for 35 of the displaced universities.

“A significant number of HEIs displaced in 2014 continue to function in 2025, having modernized infrastructure, expanded academic offerings, and strengthened international ties.

“While repeated relocations almost always entail further losses of resources and personnel, they do not necessarily lead to institutional decline; in some cases, they have instead triggered transformation, the formation of new teams and hubs, and greater adaptability,” the authors write.

A number of institutions were displaced in name only – effectively becoming ghost universities with no discernable operations or active staff. Others merged while some, like BSPU, managed to adapt – and sometimes thrive.

“We organise meetings, conferences offline in different places where we can meet safely and our staff and students use labs also all over the world,” Professor Sychikova says.

“Because of this, we have better opportunities even when we work in Berdyansk, because surely no university in the world has the complete range of equipment that its researchers would like to use. Universities with some of the best labs in the world have helped us because we are Ukrainians. It’s very important.”

Since the university had been forced to relocate, laboratories and campuses around the world had opened their doors to academics in exile – providing access to equipment and collaboration with colleagues that would never have happened otherwise.

This had resulted in BSPU scientific publications increasing since 2022, Professor Sychikova says. While the goodwill towards displaced Ukrainian staff had been exceptional, the principles of collaboration and benefits of not being limited by campus boundaries were a significant consideration for all universities.

“The universities without walls concept means recognizing that universities today have no real borders or barriers — the world is open and ready for collaboration. We should not limit ourselves to existing resources — we must think in terms of new possibilities,” she says.

Students celebrate beside the sea at Berdyansk prior to occupation.

Almost every Ukrainian has experienced loss, injury or, at best, a near miss and the attendant trauma means that BSPU places a huge focus on mental health and wellbeing.

Prior to occupation, staff and students still had mental health issues, but trauma was far less common and mental health issues still had some stigma.

Recognising the loss of loved ones, homes, workplaces and lifestyle for many, BSPU introduced a range of new initiatives. The university established an online coffee shop, for staff and student to drop in and share a virtual coffee and a psychological service, providing support. Staff also contact each student separately via phone each day, checking in to hear how they are going.

Sometimes the psychological online café “I’m Here” travels to different cities and holds

offline sessions.

A major risk from the new operational approach is exhaustion and burnout. The stress of war on the personal and professional lives of staff had also meant the University had a very strong focus on supporting and seeking to strengthen the mental health and wellbeing of staff and students.

“Psychology has been firmly at the top of the most popular educational programs since the start of the full-scale war amongst displaced universities – and that is no coincidence,” Professor Lyman said.

The university had introduced or revised curriculum for a range of new subjects relevant to the war effort and post-war recovery – with the new subjects driven by community demand and attracting significant enrolment growth.

The university must teach a range of mandatory courses for all students, relating to safety, evacuation, tactical medicine and pre military training.

Students undertake mandatory first aid training.

The surge in interest in aspects of psychology had led to the development of new programs. The BSPU team maintain a clear vision of what it will take to rebuild lives in Ukraine when the war eventually finishes.

“We have opened a new program called Post-War Socio-Psychological Rehabilitation, which is in high demand,” Professor Sychikova said.

“People in Ukraine have begun to seek psychological help much more often — something that used to be somewhat stigmatized in our society.”

Mental health has become a key focus not only for research within BSPU but also operations – and had changed the nature of Ukrainian society.

“We are facing extremely high levels of burnout and anxiety, which naturally affect work and study processes.

“We are also rethinking the concept of inclusion and vulnerable groups. Ukraine today is a country of people with disabilities and veterans. But we now also consider vulnerable those who have experienced loss or trauma, migrants, internally displaced persons, and people with family members fighting at the front. We must learn to respond appropriately, to communicate, and not to be afraid of these conversations.

“I remember after the war began in 2014 being afraid to interact with those who returned from the front. They were wounded, concussed, and often not socially adjusted compared to civilians.

“Now the entire country is like that. This is our new reality. We must learn to live in a new country, with new people. Inclusion cannot be measured only by ramps — it is a matter of mindset and empathy.”

While the trauma of war is universal to BSPU students and staff, the university has not attempted to shy away from difficult topics in their teaching, despite the pain of revisiting or being immersed in the horrors of the conflict.

“We speak openly about the war, loss, and trauma. This is our way of processing what we are living through,” Professor Sychikova says.

“Ukrainian art today is deeply infused with reflections on trauma and how to endure it. It’s painful, but it’s necessary.

“Perhaps there are some things we remain silent about simply because it hurts too much to say them out loud. But at the same time, everyone is part of this war; so many have lost their homes and loved ones, and we do talk about it.

“Every morning at 9 a.m., we observe a minute of silence across the country. All of Ukraine stops. Lecturers pause their classes to honor the fallen heroes during that minute.”

While the Universities without walls pivot has given new life to BPSU and a new focus to the careers of Professors Lyman and Sychikova, their daily reality is still the everyday anxiety of at population entangled in war – with a hole where the normal patterns of life in peacetime Berdyansk used to be.

Many of Professor Sychikova’s friends remain in occupied territories, contactable

only through an unreliable phone service and she wrestles with the reality that

she cannot know when or if she will see them again.

She now lives about 1,000 kilometers from Berdyansk in Western Ukraine, with her

son now enrolled in a university nearby. Most of her weeks are spent living out

of a suitcase, away from her new temporary family base in western Ukraine.

In addition to visiting students, staff and colleagues across Ukraine, each of the four BSPU leaders spends three weeks at a time helming the organization from Zhaporizhzhia on rotation.

“Officially, the university has been relocated to Zaporizhzhia, but that city is practically on the front line. It is extremely dangerous there — constant shelling and bombings with missiles and aerial bombs. So most of our community is not physically present in Zaporizhzhia,” Professor Sychikova says.

“As the university’s leadership (the rector and three vice-rectors), we agreed to take turns being on campus. Each of us spends about three weeks there at a time, living and working in rotation.”

As the international relations coordinator for BSPU, Professor Lyman is allowed short trips outside Ukraine to ensure the ongoing work of the University, but must be back in case he is called up for military duty and lives with his family in Kyiv.

The capital is much further from the front, but not far enough to still be under constant threat of aerial attacks and blackouts, forcing people to shelter in bunkers for long periods two or three times per week.

“The aerial terror of Kyiv continues to this day: the Russians launch more and more missiles and kamikaze drones over the city. But we continue to live in Kyiv,” Professor Lyman said.

In addition to visiting students, staff and colleagues across Ukraine, each of the four BSPU leaders spends three weeks at a time helming the organization from Zhaporizhzhia on rotation.

“Officially, the university has been relocated to Zaporizhzhia, but that city is practically on the front line. It is extremely dangerous there — constant shelling and bombings with missiles and aerial bombs. So most of our community is not physically present in Zaporizhzhia,” Professor Sychikova says.

“As the university’s leadership (the rector and three vice-rectors), we agreed to take turns being on campus. Each of us spends about three weeks there at a time, living and working in rotation.”

As the international relations coordinator for BSPU, Professor Lyman is allowed short trips outside Ukraine to ensure the ongoing work of the University, but must be back in case he is called up for military duty and lives with his family in Kyiv.

The capital is much further from the front, but not far enough to still be under constant threat of aerial attacks and blackouts, forcing people to shelter in bunkers for long periods two or three times per week.

“The aerial terror of Kyiv continues to this day: the Russians launch more and more missiles and kamikaze drones over the city. But we continue to live in Kyiv,” Professor Lyman said.

The implications of the BSPU transformation for other institutions are immense.

If a university can lose its campus, its research infrastructure and most of its resources, and yet then increase its research performance, what message does that have for institutions in safer climes across the world?

Sure, you can dismiss the success as driven by goodwill from international actors which could evaporate post-war. However, that seems narrowminded and over hasty. Who can pretend that there are not opportunities for an institution like BSPU to continue collaborations?

Embedding researchers in offshore teams on a large scale, negotiating access to world-class research infrastructure and fast-tracking progress with less focus on borders clearly offers potential to drive better outcomes – as the BSPU experience has shown.

The BPSU team aim to catalogue insights that can be relevant to universities across the world, preparing to withstand crises and maintain operations and impact.

“Universities in different countries, from time to time, challenged by natural crises or disasters, and the experience of Ukrainian universities, including experience of relocation, can be useful for academia all over the world,” Professor Sychikova says.

Displaced Ukrainian universities seek support, but also seek to analyse and report on their experience with disruption, new models of operation and engagement. Not every university will find itself in a war zone, but there are plenty of other crises that can threaten the operations of an institution – natural disasters, government interventions or funding shortfalls.

Likewise, while BSPU’s identity was closely linked to its buildings and location, to a point of even featuring the main building’s castle-like walls on the logo, staff have found that the university can continue to thrive and contribute to Ukrainian society while operating entirely out of borrowed campus space in another university. Sure, it’s neither comfortable nor optimal in the long term, but given the underutilisation of university campuses, why wouldn’t two or more higher education institutions consider operating out of the same campus? If there was greater timetabling flexibility, institutions could double the usage of many facilities, operating extended hours and on weekends – while potentially halving the costs of maintaining facilities.

Is the Australian passion for owner-occupied real estate artificially inflating the cost of degrees; reflected in the insistence that each university must own its own campus? Do we need campuses at all?

The transformation to a truly community-centric university requires far more reform than Australian institutions currently countenance. For a start, hierarchy still exists, but status at BPSU went out the window when staff fled empty handed along the same road of death as students – equalised by common experience and dispossession. Staff have heavily prioritised mental health and wellbeing not only of students, but also of each other, recognising the diverse, often traumatic experiences that many have faced. Courses are run not just online, but also with intensives that travel from city to city – bringing classes and engagement to the student.

Curriculum is rapidly changing in line with community needs. No committees are required to decide whether it’s a good idea to teach emergency first aid to students who have to run to bomb shelters several times a week to evade aerial bombardments. In order to keep existing year-to-year, the university staff must understand and respond to community demand, in terms of both courses offered and research priorities set. There is no luxury of time or treasure to fund prevarication or ego.

Anecdotally, BSPU staff report this has significantly increased the social licence of the university – forging deep bonds and networks with the displaced residents of Berdyansk and surrounds.

Students and staff spend a lot of time in bomb shelters – whether their city is under attack, or simply under threat, they must shelter until danger has passed. Teachers and students must frequently – sometimes daily, shelter from missiles all night and many have difficulty sleeping, but must front up to class the next day.

In the first month after relocation, everyone believed they would be returning to Berdyansk soon.

As months turned into years of displacement, that belief has been hard to sustain – but is still important.

“We need to say that we are still going back home,” Professor Sychikova says. “We still plan, wish and desire to be back home in Berdyansk.”

On a broader level, it is hope that the war will end, and end in victory is that keeps many going.

“Hope is, in fact, the main rule for survival under the kind of stress we live in,” Professor Sychikova says.

“I think it’s really about responsibility — the feeling that “I have no right to lose hope,” because it’s up to us to carry it and share it with others. Of course, there are moments when dark thoughts come — about the future of the university, whether we will survive, whether the ministry might decide to merge us with another institution. But I quickly push those thoughts away: I am needed here and now, and I must do everything I can to save what we have, because I bear great responsibility.

“It also helps to remember that the university is a community — we even call it a university family. When you see it that way, you realize that we are many, and our strength lies in unity.

“Perhaps most importantly, it’s about support. The empathy and solidarity of colleagues, friends, and other countries. Before, we didn’t feel as deeply how essential and powerful support can be.”

“Now, after losing so much, we’ve realized that we’ve gained something even more important — a sense of human connection,” Professor Sychikova says.

“I believe this has become one of the core values on which this fragile world still stands.”

“Now, after losing so much, we’ve realized that we’ve gained something even more important — a sense of human connection,” Professor Sychikova says.

“I believe this has become one of the core values on which this fragile world still stands.”

Professors Yana Sychikova and Igor Lyman are coming to Australia to share their experiences, featuring in a symposium on future opportunities for Universities Without Walls in Australia.

Hear from Yana and Igor in Canberra on 23 Feburary 2026, followed by insights from multiple higher education leaders from across Australia. Tickets are limited – book via button below.

Subscribe to us to always stay in touch with us and get latest news, insights, jobs and events!!